Summary

This article provides an overview of Module D provided in construction production EPD. It describes the background to Module D, supplementary information in the EPD which aims to provide transparency on the environmental benefits resulting from reusable products, recycled materials and recovered energy leaving a product system, However, the paper identifies and explains a number of serious limitations with Module D and its use listed below. These limitations highlight the importance of careful consideration when using Module D in environmental assessments and comparisons, and this paper provides guidance on the appropriate use of Module D.

Inconsistency with Other Modules:

- Module D should never be aggregated with Modules A-C, due to different system boundaries and allocation approaches, leading to inconsistencies in methodology.

- If Module D was aggregated with Modules A-C, it would result in no difference between the impact of a primary product and a recycled product which are both recycled at end of life, failing to recognise the benefits of a circular economy.

Overestimation of Future Benefits:

- Module D uses current impacts to assess the avoided impacts of primary production, which may significantly overestimate benefits due to expected decarbonization of industrial processes by 2050.

Limited Recognition of Circular Economy:

- Module D only recognises the benefits of recovering primary material. It does not reflect the benefits of recycling already recycled materials, or reusing reused materials, both of which will be crucial for a circular economy.

- For recycled materials which are reused, Module D may not show any benefits at all.

Introduction

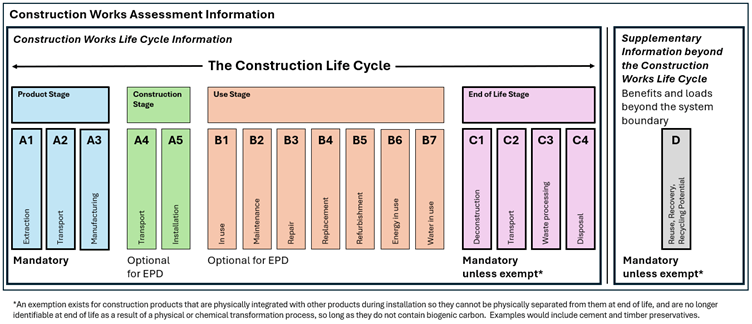

If you look at a construction product Environmental Product Declaration (an EPD for short), then you will see that the environmental impacts are broken down into life cycle stages and modules, as in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 The Life Cycle Stages and Modules used for construction product EPD

According to the standards for construction product EPD, EN 15804 and ISO 21930, the construction life cycle covers the Product Stage (A1-A3), the Construction Stage (A4-A5), the Use Stage (B1-B7) and the End-of-Life Stage (C1-C4). In addition, most construction product EPD must also report Module D, but what does this module report and what can it tell us about a construction product?

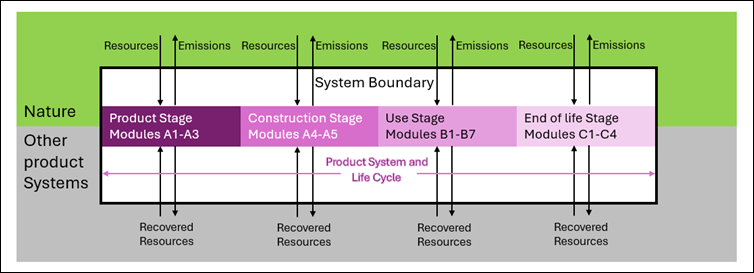

Module D is supplementary to the information provided about the product’s life cycle and reports the “Benefits and loads beyond the system boundary”. Defining a system boundary is one of the requirements when using life cycle assessment (LCA) – the science which underpins EPD. It is used so that you know when to start measuring impacts and when to stop measuring them, and it needs to be defined consistently for all the different resource, material and emission flows within the product system. The system boundary needs to be defined both with nature, and with other product systems, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 Diagram illustrating the system boundary to nature and to other product systems

In construction product EPD, we account for all the human related processes starting from the extraction of resources from nature such as the biomass, renewable energy, fossil fuels, minerals, or water used to make products, maintain them, or dispose of them; we also track any the emissions which are released to nature, such as CO2 emitted to air, pollutants released into rivers or the sea, or wastes which are deposited on land, as shown in the top half of Figure 2.

We also need to define the system boundary to other product systems. This system boundary applies when we use recovered resources within the product system, such as recycled or reused materials, secondary fuels or recovered energy, or when we recover wastes that we have produced, such as when we generate recycled or reused materials, secondary fuels or recovered energy within the product system, as shown in the bottom half of Figure 2.

For construction product EPD, the system boundary between products systems is defined when:

- the recovered material, product or fuel is commonly used for specific purposes; AND

- a market or demand, shown, for example by a positive economic value, exists for such a recovered material, product or fuel; AND

- the recovered material, product or fuel fulfils the technical requirements for the specific purposes for which it is used and meets the existing legislation and standards applicable to products or secondary fuels.

EN 15804 also requires that the“use of the recovered material, product or construction element will not lead to overall adverse environmental or human health impacts”. Waste which has been recovered and meets these conditions has reached the “end-of-waste state”, and due to the identical requirements of the EU Waste Framework Directive, this point is also commonly where waste changes its legal status to that of a product which has to comply with relevant product legislation, for example the REACH Regulation[1].

As an example, if a construction product uses recycled plastic, then the impact associated with the recycled plastic will only be accounted for from the point at which the recycled plastic reaches the end-of-waste state, normally once it has been granulated. And if waste plastic is produced and recovered during the construction product life cycle (for example at end of life), then the impacts will be accounted for until the waste plastic reaches the end-of-waste state, again, once it has been granulated. This means the system boundary for recycled plastic is in the same place whether it is an input or an output to the system, there is no double counting. Similarly, if transferring any impacts from primary production to materials recovered at the end of life – known as allocation – the LCA rules require that the approach must be consistent for the whole system, so that an input and output of the same recovered material would have an identical impact. In EPD for construction products, the “cut-off” approach (also known as the “100-0” or “recycled content” approach) is used. This means that for re-used and recycled materials and secondary fuels that cross the system boundary, for example recovered materials from construction or demolition, no impacts from their original life cycle are allocated or transferred to this later life cycle – they enter the next product system free of burden. This follows the “polluter pays principle”, where those generating waste have all the impacts associated with producing and disposing of it.

What is Module D?

EN 15804 assigns all the impacts associated with producing and treating end-of-life waste to the producer of the waste, and they are not able to allocate or transfer any of the impact of primary production forward to the potentially many recycled product life cycles in the future. Alongside the life cycle impacts of the product system reported in modules A1-C4, Module D is intended to recognise the benefits of designing for reuse, recycling and recovery, and indicates the potential benefits from the avoided use of primary materials, whilst taking into account the potential loads associated with recycling and recovery processes beyond the system boundary.

From this point of view, Module D mirrors an alternative approach to allocation of primary impacts, where these are allocated from the primary product system to future recycling using an allocation approach called the “avoided burden” approach (also known as the “0-100” or “end-of-life recycling” approach). We have discussed above how LCA studies must use a consistent system boundary and allocation approach for recovered materials. This is provided with the “cut-off” approach used for assessing modules A1-A5, B1-B7 and C1-C4 over the life cycle of the product – if all the life cycle stages and modules have been assessed for the product based on the relevant building context, then the impacts can be aggregated to give the full impact over the life cycle using a consistent system boundary and allocation approach. Sometimes however, we see Module D aggregated with Modules A-C. This is really problematic, as it both expands the system boundary for outputs so that it is not consistent for inputs and outputs, and also means that the “cut-off” approach used for inputs is not consistent with the “avoided burden” approach used for outputs in Module D. For this reason, the impacts from Modules A to C must never be aggregated with those from Module D.

An example of the problem with aggregation can be seen if we look at the impact of a plastic product made of primary material which is recycled at end of life, substituting the same primary plastic. The benefit calculated in Module D will be equivalent to the impact of primary production in A1-A3, only deducting the losses from the recovery process. This means that if we aggregate Modules A-C and Module D, that most of the impact of primary production in A1 is cancelled out in Module D, and the only impact for the product is from product processing in Module A3, the impacts in modules A4-C4 and any processing to reach the point of substitution in Module D, plus the primary impact of manufacturing the small amount of material lost through recovery. If we compare this to the impact of the same product made of the same recycled plastic, which is recycled in the same way at the end of life with the same losses, and aggregate the impacts of modules A-C and Module D, these two plastic products will have practically the same impacts aggregated over Modules A-D, despite having very different impacts in reality. Aggregating Module D with Modules A-C provides no recognition of the circular economy benefits of using recycled materials today, nor of the benefits of circular products which are both made of recycled content and recycled at end of life.

A further problem with Module D is that for most construction products, their end of life will not be for many years into the future. However, Module D uses current impacts to assess the avoided impacts of primary materials (the benefits) and the impacts of recovery (the loads). As we expect that many industrial processes will be significantly decarbonized by 2050, we can see that the calculation of benefits and loads using current impacts is not conservative, but very likely Module D over-estimates the benefits that will occur in the future from recycling and recovering primary materials.

Additionally, Module D only accounts for the benefits and loads associated with “net output flows” of recovered materials. This means that for an output of recovered material from a product system, which will go to substitute future primary production, any input to the product system of the same recovered material must be deducted from the output to arrive at the net output flow (the output minus the input of the same recovered material), and only this net output flow can be considered in Module D. This means that whilst a product made of primary material that is 100% recycled at end of life can report the benefits in Module D, a product that is made of the same 100% recycled material and is 100% recycled at end of life cannot report any benefit, even though there will be exactly the same benefit in the future in terms of avoided primary production. Module D is sometimes talked of as providing information in EPD in relation to the circular economy, but the fact that it only recognises the benefit of recovering primary material at end of life, and not the benefits of recovering recycled materials (which would be more recognisably circular), means that Module D is not a good reflection of the circular economy, as recycled products which are themselves recycled show no benefits in Module D.

Module D for reused products

The examples above have considered recycling, but for reuse, the results in Module D can be even more surprising. For products made of primary material, reusing them at end of life will show big benefits in Module D. However, for a recycled product which is reused at the end of life, some interpretations of EN 15804 would consider the material for reuse is made of the same secondary material used to manufacture the recycled product. If this interpretation is used there would be no net output of secondary material so Module D would show no benefit, failing to recognise the significant benefits of reuse expected within a circular economy. To address this inconsistency, the second version of the RICS Professional Standard for Whole Life Carbon in the Built Environment has stated that when a recycled material is reused, the material for reuse should not be considered as the same secondary material, and the benefit of reuse should be calculated on the net output of material for reuse, which would give a similar result in Module D to the reuse of the same primary product. This approach has also be included in the most recent draft of the revised EN 15978.

How can you compare construction products using EPD?

EN 15804 provides rules for comparing construction products using EPD, which state that the comparison must be based on the product’s use in a building and its impact on the building and must consider the complete life cycle. However, EN 15804 also allows for comparisons at the sub-building level, e.g. comparing products directly, perhaps for just one life cycle stage. In such cases the principle that the basis for comparison is the assessment of the whole building over its life cycle, must be followed by ensuring that for any comparison:

- the same functional requirements for the product as defined by legislation or in the client’s brief are met, AND

- the environmental performance and technical performance of any excluded assembled systems, components, or products are the same, AND

- the amounts of any excluded material are the same, AND

- excluded processes, modules or life cycle stages are the same; AND

- the influence of the product systems on the operation and impact of the building are considered;

- the elementary flows related to material inherent properties, such as biogenic carbon content, the potential to carbonate or the net calorific value of a material, are considered completely and consistently, as described in EN 15804.

In this way, if you were comparing two floor coverings using EPD, then the products could be compared using the impacts provided in their EPD if:

- Both products can provide the functional performance required by the client, and any relevant legislation – this does not mean they need to provide the same functionality, so long as the required functionality is met.

- The adhesive to fix the flooring could be excluded so long as the amount of adhesive was the same and the environmental and technical performance of the adhesive was the same.

- The life cycle modules for installation (A5), maintenance (B2), repair (B3), replacement (B4) and refurbishment (B5) could be excluded if they would be the same for both products, i.e. if there would be the same amount of wastage, they would be cleaned in the same way, and would last for the same amount of time.

- The module for transport (A4) would need to be included if the products came from different locations with different transport impacts;

- The modules for end of life (C1-C4) would need to be included if the products had different masses per m2 so had different end of life impacts, or if one product could and would be recycled and the other would be disposed of using energy recovery.

- If for any reason one of the floor coverings would influence the operation of the building differently (for example influencing the availability of thermal mass), then this would need to be accounted for in the comparison.

If the conditions for comparison are met, then the information from the EPD for the relevant processes and information modules could be used for the comparison of the two products. As Module D provides supplementary information beyond the construction works life cycle, it does not have to be considered within any comparison of construction products using EPD. But if Module D is considered as part of any comparison, as explained above, great care should be taken, and certainly it is clear that the impacts in Module D must not be added to the impacts of the remaining modules within the product life cycle. If one the compared products uses recycled inputs, it must be recognised that Module D will not show any benefits of recovering this product, although any recovery will clearly have similar benefits to recovering the product made of primary material. And if you are looking to recognise the benefits of moving towards a circular economy, remember, Module D only reflects the benefits of the future recovery of primary material. In addition, any benefits reported in Module D are likely to be a significant overestimate of the actual benefits in the future, due to industrial decarbonisation.

Acknowledgements

This article was written by Dr Jane Anderson with funding from Interface.

[1] Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals Regulation, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02006R1907-20240606

Thanks Jane, really useful!

Thank you for a great article! There are many very important issues mentioned but I would not be so pessimistic about the usefulness of Module D. I think that many of the challenges can be solved:

– It is already mandatory to report Module D separately according to CEN/TC350 standards

– We can use the projected impacts in the future for the calculation of substituted emissions in Module D (see the French RE2020 methodology)

– Recycled materials which are reused in the future can show the benefits correctly, they only need to be treated separately as different secondary materials. This is already used in steel industry’s EPDs and now also in World Steel Association’s methodology.

My point is that instead of waiting for new circularity metrics to be widely accepted in the EPDs, let’s make the best from what we already have. Let’s clarify and harmonize the rules for Module D so it can be more useful.

Thanks Jane for your honest review of Module D.

From a metals perspective, it is the incompatibility between the system boundary of the building defined by TC350, and the theoretical ‘infinite’ life of metals that gives rise to the scope and methodological challenges that Module D attempts to address.

I agree that the current net output flow approach based on the avoided impacts of primary production risks overestimation of future benefits, certainly for long-lived products like buildings. Furthermore, the net-flow approach is not a satisfactory metric for measuring and promoting circular economy thinking.

There is a lack of understanding and consistent application of the in the end-of-life formula for Module D2 in EN 15804. If equation D.6 is applied separately to recycled and reused flows, then the benefits of, for example, reusing already recycled materials can be demonstrated using Module D. Whereas, if they are not differentiated, the net-flow of secondary materials is zero and hence Module D2 is zero. TC350 need to clarify this point. A better approach and metric are required to promote circular economy thinking.

I fail to understand why the LCA system boundary cannot be extended to include more than one building life cycle, after all this approach is adopted for temporary works by both RICS and IStructE who advocate a default of three (re)uses for plywood formwork and 20 (re)uses for steel formwork. Why are temporary works treated differently from permanent works?

By expanding the system to include two or more building lifecycles the benefits of highly recycled and highly reusable construction products can be robustly demonstrated.

The very big difference between temporary works and projects is the timescale. 3 reuses of plywood formwork and 20 reuses of steel formwork are not likely to take more than a year or couple of years at most, whereas two building lifetimes are at least 100 years, and in most cases many more. If it is already overstating the benefits in MOdule D in 20 years if we are anywhere close to our net zero targets, then looking at multiple lifetimes is surely more problematic and much more uncertain.

We need to be reusing and upcycling now, and finding new sources of metal scrap – for example the US recycling rate for steel cans is only 70% (https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/ferrous-metals-material-specific-data), rather than giving overstated credits to products which will only be available for recycled many years into the future.

I accept that the timescales for temporary and permanent works are very different but how does this justify a different approach for dealing with the reuse of both temporary and permanent works? Surely the approach should be consistent? Factor in decarbonisation for future benefits but keep the approach consistent.

On ferrous scrap availability, hopefully you have seen the new IStructE publication launched last week The role of scrap in steel decarbonisation – The Institution of Structural Engineers